The Art of US Coin Designs 的钱币相册

The large cent was the coin of local commerce. There was criticism of the earlier Chain cents, so the first Mint Director David Rittenhouse, hired Joseph Wright to do a redesign. Wright drew inspiration from French medalist Augustin Dupre's 1783 Libertas Americana Medal, facing Liberty to the right and "tamed" her wild hair. The Phrygian cap was added as an ancient symbol of freedom. The reverse design was revised from the chain to a recognizable laurel wreath. Robert Scot completed the work, making several modifications to the design between 1794 and 1796.

In 1856 the large cent was reduced in size to the penny diameter we know today with the Flying Eagle cent. Chief Engraver James Longacre's obverse of an eagle in flight is based on that of his predecessor, Christian Gobrecht’s dollar, struck in small quantities from 1836 to 1839. According to Cornelius Vermeule, the flying eagle motif, when used in the 1830s, was "the first numismatic bird that could be said to derive from nature rather than from colonial carving or heraldry". Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, when commissioned in 1905 to provide new designs for American coinage, sought to return a flying eagle design to the cent, writing to President Theodore Roosevelt, "I am using a flying eagle, a modification of the device which was used on the cent of 1857. I had not seen that coin for many years, and was so impressed by it that I thought if carried out with some modifications, nothing better could be done. It is by all odds the best design on any American coin."

Longacre was asked to start preparing new designs for the cent due to strike problems with the Flying Eagle cent. He describes his use of the feathered headdress: "It is more appropriate than the Phrygian cap, the emblem rather of the emancipated slave, than of the independent freeman, of those who are able to say ‘we were never in bondage to any man’. I regard then this emblem of America as a proper and well defined portion of our national inheritance; and having now the opportunity of consecrating it as a memorial of Liberty, ‘our Liberty’, American Liberty; why not use it? One more graceful can scarcely be devised. We have only to determine that it shall be appropriate, and all the world outside of us cannot wrest it from us.” Cornelius Vermeule had mixed emotions about the Indian Head cent: "Longacre enriched the mythology of American coinage in a pleasant if unpretentious fashion.” In another comparison, Vermeule suggested, "far from a major creation aesthetically or iconographically, and far less attractive to the eye than the [flying eagle], the Indian head cent was at least to achieve the blessing of popular appeal. The coin became perhaps the most beloved and typically American of any piece great or small in the American series. Great art the coin was not, but it was one of the first products of the United States mints to achieve the common touch.”

Timed to commemorate Lincoln's 100th birthday in 1909, the Lincoln Cent was the first U.S. circulating coin to depict the image of a President. The White House had commissioned Victor Brenner to immortalize Roosevelt on a medal for the Panama Canal Commission. As a result of his acquaintance as well as his prior work on Lincoln portraits, he was commissioned to adapt his Lincoln medal design for use on the one cent coin. Although this coin’s development was overseen by Roosevelt himself, Brenner’s design is rather staid overall. it ultimately established a precedent according to which all circulating denominations would come to bear the likenesses of politicians by the end of the 1940s. Vermeule had high praise for Brenner: "He has succeeded in conveying the feeling that a photograph of Lincoln has been turned into a three-dimensional experience in metal...” Vermeule was also impressed by the artist’s modest design for the coin’s reverse: two ears of grain flanking a series of inscriptions. This, he said, "took much thought on the part of the artist" and served well as a complement to the equally simple obverse.

Lobbying by nickel mining interests led the Mint Director to order Charles Barber, the Mint’s Chief Engraver, to produce uniform designs for a new cent, three-cent nickel, and five-cent piece. The Liberty Nickel, was approved, going into production in 1883. Simple in design, with the Liberty head on the obverse and a Roman numeral V on the reverse within a wreath, signifying the value of five cents. The artistically conservative design captures the essence of the late Victorian era.

The native American theme first seen in Longacre’s Indian cent was later echoed in James Earle Fraser’s Buffalo Nickel design, showing a Native American chief on the obverse and a buffalo on the reverse The Indian and Buffalo motif proved quite popular both with Fraser’s contemporaries and throughout the years. Vermuele praised this coin as “perhaps the most beloved and typically American of any piece great or small in the American series.” He also noted that Fraser was “[t]he first die-designer to represent the Indian with dignified accuracy.” The first year variety Type 1 version of this coin is identifiable by the raised mound of earth that the Bison stands on. Other unique attributes include its textured fields and also the omission of the motto “In God We Trust.”

The 1839 Gobrecht Dollar with the Thomas Sully designed Seated Liberty sans stars on the obverse and the William Peale designed flying eagle on the reverse is up there on my list of favorite designs. Unfortunately, that coin is out of reach, so this half dime along with the flying eagle cent are my mini Gobrecht Dollar Sully’s Seated Liberty design was executed by Mint engraver Christian Gobrecht, a man of great technical skill. Its neoclassical appearance accurately reflected Americans' artistic taste in the mid-19th century. The Seated Liberty half dime is the smallest in size and lowest in denomination of the six series of coins bearing the Seated Liberty designs.

In 1915 the Department of the Treasury held an open contest to solicit new designs for the dime, quarter, and half dollar. For the new dime, sculptor Adolph Weinman, who was also a student of Saint-Gaudens. submitted the winged liberty design as the winning entry. Weinman's dime depicts Liberty with a wreath of tight curls, and wearing a traditional pileus, or Liberty cap. His depiction of the pileus as a winged cap has provoked comparisons with Roman Republic denarii, which Vermeule considered superficial. Weinman wrote that he considered the winged cap to symbolize "liberty of thought". Vermeule suggests that one reason for the use of wings was that Weinman, in common with many in the tradition of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, liked the effect of feathers done in relief. The reverse depicts a fasces, the object carried by lictors, who accompanied Roman magistrates; on the coin it represents war and justice. It is contrasted with a large olive branch symbolizing peace. According to Breen, "Weinman's symbolic message in this design ... was clearly an updated 'Don't tread on me.” The wings adorning Liberty's head on the obverse design of this coin reminded many of the Roman messenger God Mercury who wore wings at his heels, and suggesting that is how this coin came to be named.

Submitted by sculptor Herman MacNeil, the new Standing Liberty quarter design won the 1915 open contest held by the Department of the Treasury. According to Vermeule, "Liberty is presented as the Athena of the Parthenon pediments, a powerful woman striding forward" and states that, but for the Stars and Stripes on her shield, "everything else about this Amazon calls to mind Greek sculpture of the period between Pheidias to Praxiteles, 450 to 350 BC." Vermeule suggested that the flying eagle on the reverse is simply that of the 1836 Gobrecht dollar, seen flying from left to right instead of the opposite way, as on the earlier piece. He also noted that the reverse marked the beginning of the end (at least for that era) for naturalistic depictions of eagles on US coins, stating that those after 1921 tended to present a heraldic appearance instead.

The Washington quarter first produced in 1932 was originally intended to be a one-year coin to commemorate the 200th anniversary of George Washington's birth. Laura Fraser won the contest to create the quarter. This made her the first woman chosen to design a coin for national circulation. However, despite the strong support her designs gained from the Commission of Fine Arts, the Treasury Department instead selected designs by John Flanagan, whose portrait of Washington remains in use on the quarter today. It was not until Jane Goodacre won the competition to design the obverse of the Sacagawea dollar in 1999 that a circulating U.S. coin was designed by a woman. Due to the Great Depression, no Washington quarters were produced in 1933. However, the issue proved to be so popular that the design was permanently adopted in 1934 and is still in use to this date.

The Capped Bust Half Dollar was designed by John Reich, an immigrant from Germany who came to the United States in the early 19th century. Reich's design was used on every coin from the half cent through the half eagle, the lowest and highest denominations then being produced. His basic obverse design was a left-facing portrait of Liberty with curly hair tucked into a mobcap, a cap with a high, puffy crown. This likeness is often referred to as the "Turban Head" portrait. The reverse shows a naturalistic eagle with a shield superimposed upon its breast. C. Overton put into words the affection he felt for his favorite coinage series "finding them not only beautiful and fascinating, but ... there exists a myriad of die varieties and sub varieties..." that have been of endless interest for collectors.

Mint Director Robert M. Patterson had his own vision of the emblematic Liberty, and it didn't include portraits, as on the coinage to date. He favored the rendition of Britannia. and immediately assigned Chief Engraver William Kneass to do a sketch using a similar concept that was developed by Thomas Sully. After Kneass' died from a stroke, Christian Gobrecht went to work to bring Patterson’s and Sully’s ideas to life. Vermeule tied the appearance of the obverse to neoclassicism, noting the resemblance of Gobrecht's Liberty to the marble statues of ancient Rome. He also noted, "it becomes almost painfully evident that similar sources were consulted both by the engravers of United States coins in Philadelphia and by the cutters of tombstones from Maine to Illinois.” He also says of the design, “[Liberty] has lost much of her plastic quality, becoming flatter and more like an engraving than a statue….Clutching her ridiculous little hat on a pole and the small shield nestling in the drapery at her side, Liberty looks anxiously over her shoulder as if a horde of Indians were sprinting…toward her.” However, he also notes: "Conceived in the classical tradition, nurtured by a triad of gifted artists, the seated Liberty presided over the coinage of the United States with an individuality matching that of the pioneers, soldiers, merchants, writers, and craftsmen who were making the republic great". Although reminiscent of Greek and Roman forms, it is thoroughly an American creation. The resulting design dominated silver coinage for over 50 years.

In addition to the Mercury Dime, Sculptor Adolph A. Weinman created the design for the half dollar. He depicted an image of a confident female figure of Liberty in flowing robes, striding across the American landscape before a rising sun. The reverse of the coin was dominated by a bold eagle poised for flight, maintaining the tradition of the image of Liberty on the front and the eagle on the reverse. Vermeule wrote that the Walking Liberty half dollar "really treat[s] the obverse and reverse as a surface sculptural ensemble. The 'Walking Liberty' design particularly gives the true feeling of breadth and sculptural services on the scale of a coin." On the reverse, Vermeule admired the eagle, which dominates but does not overwhelm the design, and stated that the bird's feathers are "a marvelous tour de force", showing the influence of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, under whom Weinman studied. He characterized the Walking Liberty half dollar to be "one of the greatest coins of the United States—if not of the world".

The Draped Bust dollar obverse was designed by noted artist Gilbert Stuart in an attempt to elevate U.S. coinage designs to "world class" stature. This design marked a maturing of the "young" Liberty of the preceding Flowing Hair design to a more "matronly" concept of the emblematic national symbol. In 1798, the young hatchling eagle seen on the reverse of the earlier dollar was replaced with an older and more naturalistic eagle, and one that was more in keeping with heraldic iconography. Cornelius Vermeule characterized the Draped Bust version of Liberty as "a buxom Roman matron" and observed that "her full face has been endowed with a Roman dignity that recalls some massive marble bust of Minerva or Dea Roma, goddess of Rome and her empire ..."

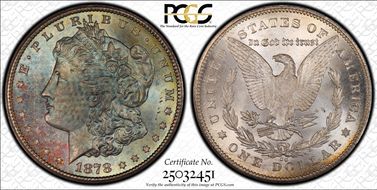

The Morgan dollar was the first standard silver dollar minted since production of the previous design, the Seated Liberty dollar, ceased due to the passage of the Coinage Act of 1873, which also ended the free coining of silver. However, mining interests lobbied to restore free silver, which would require the Mint to accept all silver presented to it and return it, struck into coin. Instead, overriding a presidential veto, the Bland–Allison Act, passed in 1878, requiring the Treasury to purchase between two and four million dollars' worth of silver at market value to be coined into dollars each month. The US Mint’s Assistant Engraver George T. Morgan was the designer. The obverse depicts a profile portrait representing Liberty, while the reverse depicts an eagle with wings outstretched. Vermeule describes Morgan's dollar as “a refreshing step away from the standard Gobrecht-styled seated Liberty and 'sandwichboard' eagle, but the decisive moment of revolution in American numismatic art had not yet arrived.”

Inspired by the peace that followed World War 1, Anthony de Francici designed the winner of the competition for a new dollar. The young sculptor, a pupil of James Fraser, beat out other designs submitted by Hermon MacNeil, Victor D. Brenner and Adoph Weinman, who had all designed previous U.S. coins. Despite the hurried execution, the reverse is a work of genuine quality and well reflects the mood of the American people with respect to the end of the war. The eagle is serenely glancing toward the scene of victory and peace, something that could be understood by all. The bird is perched atop a mountain, thus symbolizing strength and determination to watch out for those who would destroy that hard-won peace. De Francisci's obverse is loosely based on the Saint-Gaudens' head for the gold eagle of 1907 and certain other works by the same artist. Breen wrote that the radiate crown that the Liberty head bears is not dissimilar to those on certain Roman coins, but is "more explicitly intended to recall that on the Statue of Liberty." De Francisci's wife, Teresa Cafarelli, who served as a model, related that when she was five years old and the steamer on which she and her family were immigrating passed the Statue of Liberty, she was fascinated by the statue.

The Sacagawea Dollar coin was released in honor of Sacagawea, the Shoshone woman who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their expedition to the Pacific Ocean. The obverse depicts Sacagawea with her infant son, Jean Babtiste Charbonneau, who was fifty five days old when the expedition departed Fort Mandan. The reverse of the coin was designed by Thomas D. Rogers. It features a soaring eagle surrounded by seventeen stars representing the union members in 1804, at the start of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Glenna Goodacre's artistic rendering of Sacagawea dollar won the $5,000 commission awarded by the United States Mint. Goodacre requested that her fee be delivered in Sacagawea dollars to her studio in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The dollars provided to her were different from the coins that were minted for regular circulation. The United States Mint struck them on burnished planchets that gave them a proof-like or "Specimen" appearance.

Bela Lyon Pratt, who served as Saint-Gaudens’ assistant while an art student in New York, was chosen by Theodore Roosevelt to design the $2 ½ and $5 gold denominations. Pratt overhauled the traditional and allegorical bust of Liberty to create a new, incuse design of a Native American. The obverse features the head of a Native American man, wearing a headdress and facing left. Vermeule dismissed complaints made at the time of issuance that the Indian was too thin: "the Indian is far from emaciated, and the coins show more imagination and daring of design than almost any other issue in American history. Pratt deserves to be admired for his medals and coins." Vermeule suggests that Pratt's design "marked a transition, in the 'emaciated' Indian at least, to naturalism". The reverse features a standing eagle on a bunch of arrows, its left talon holding an olive branch in place.

St. Gauden's $10.00 coin, expanded on a motif that James B. Longacre first debuted on the 1854 $3.00 gold coin. The bust on the new eagle was almost identical to the Nike head (Victory) that Saint Gaudens designed for Sherman's monument in New York's Central Park. At Roosevelt's insistence, she shed her laurel crown for a handsome, but historically impossible Indian feathered war bonnet.The reverse contains the traditional elements of an American bald eagle holding arrows and an olive branch as arranged in a formal yet lifelike manner. Although Saint-Gaudens' design for the eagle had featured Liberty in an Indian-style headdress, as with Longacre’s earlier designs, no attempt was made to make her features appear to be Native American. Vermeule, however, noted that the Indian Head eagle "missed being a great coin because Roosevelt interfered with the choice of headdress (or no headdress) for Liberty."

James B. Longacre designed the $20 Gold Liberty, amidst considerable infighting at the Philadelphia Mint between he and the Mint Director Robert M. Patterson. The design features a woman's head modeled after an ancient Greco-Roman sculpture, the Crouching Venus. His reverse reflected his training as a two-dimensional engraver. Cornelius Vermeule disliked the double eagle and other Longacre coins showing Liberty, calling them routine. He did find that the reverse "has some commendable points of heraldic imagery" and likened that side of the coin to "the frontispiece for a patriotic brochure". The Daily Alta California in May 1850 reprinted a piece from an unnamed Eastern newspaper, which said of the new piece, "we cannot say that we admire it ... [the eagle on the reverse is] imperfectly formed, and marred by some adjacent flummery intended for radiance we suppose, by which the whole thing is rendered confused".] Nevertheless, the coin was immediately successful; merchants and banks used it in trade and it became America's largest circulating gold coin.

In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt sought to beautify American coinage, and proposed Saint-Gaudens as an artist capable of the task. Although the sculptor had poor experiences with the Mint and its chief engraver, Charles E. Barber, Saint-Gaudens accepted Roosevelt's call. The $20 St. Gaudens Saint was a dramatic shift from the previous design found on the double eagle, which had featured the static head of Liberty in profile. It featured a full figure depiction of Liberty striding forward with a lit torch and olive branch in her hands. The rays of the rising sun and the Capitol building appear in the background. Encircling her are 46 stars, one for each state in the Union at that time. The new reverse design for the double eagle featured a breathtaking view of an eagle in flight with the sun below and rays rising upwards. Vermeule described this masterpiece as “perhaps the majestic coin ever to bear our national imprint.” Roosevelt loved it, exclaiming "It is simply splendid. I suppose I shall be impeached for it by Congress, but I shall regard that as a very cheap payment!"