Gobrecht's Raisinet Collection 的钱币相册

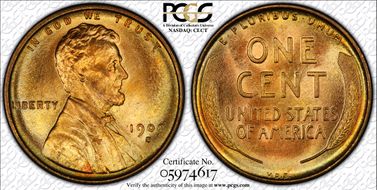

Intense luster, impressive color, NO spots, Very PQ. This is, perhaps, the most well-known collector date coin in the 20th century. With a mintage of just 484,000 pieces, the lowest of the series, it has the lowest mintage of any regular issue Small Cent, aside from the 1909-S Indian Cent. The 1909-S VDB enjoys a constant level of popularity from collectors because of its relatively low mintage, it’s first year of issue status, and the fact that 1909 was the only year the designer's initials were, at least for a while, placed on the lower reverse. The desirability of the issue is increased by its quality; unlike many San Francisco issues from the teens and twenties, the 1909-S V.D.B. tends to come well struck from fresh dies with consistent color. Calling it “The Holy Grail for Lincoln cent collectors,” David Lange, writing on the 1909-S VDB cent in his The Complete Guide to Lincoln Cents, refers to a story that is attributed to numismatic researcher George Fuld who "...recounts how coin dealer John Zug acquired some 25,000 uncirculated 1909-S V.D.B. cents directly from the San Francisco Mint at the time of their issue. Correctly surmising that these coins...would grow in value, he held onto them for several years. Around 1918, however, he decided to sell short [sic], realizing 1.75 cents apiece for his hoard. While of course we cannot be sure of Zug's motivations, perhaps he was alarmed by the restoration of Brenner's initials to the obverse of the cent beginning that year, fearing that this would lessen the value of his investment." Chief Engraver Charles Barber is often portrayed as a jealous (and even villainous) figure by imaginative numismatic writers, especially when the subject concerned designs from outside artists. Barber is frequently credited with the prompt removal of the 'prominent' V.D.B. initials from the reverse; they returned to the Cent on Lincoln's shoulder in 1918, after Barber's demise. While a valuable issue in all Mint State grades, only once the MS66 tier is reached does the '09-S VDB truly qualify as a scarcity.

Intense luster, impressive color, NO spots, Very PQ. This is, perhaps, the most well-known collector date coin in the 20th century. With a mintage of just 484,000 pieces, the lowest of the series, it has the lowest mintage of any regular issue Small Cent, aside from the 1909-S Indian Cent. The 1909-S VDB enjoys a constant level of popularity from collectors because of its relatively low mintage, it’s first year of issue status, and the fact that 1909 was the only year the designer's initials were, at least for a while, placed on the lower reverse. The desirability of the issue is increased by its quality; unlike many San Francisco issues from the teens and twenties, the 1909-S V.D.B. tends to come well struck from fresh dies with consistent color. Calling it “The Holy Grail for Lincoln cent collectors,” David Lange, writing on the 1909-S VDB cent in his The Complete Guide to Lincoln Cents, refers to a story that is attributed to numismatic researcher George Fuld who "...recounts how coin dealer John Zug acquired some 25,000 uncirculated 1909-S V.D.B. cents directly from the San Francisco Mint at the time of their issue. Correctly surmising that these coins...would grow in value, he held onto them for several years. Around 1918, however, he decided to sell short [sic], realizing 1.75 cents apiece for his hoard. While of course we cannot be sure of Zug's motivations, perhaps he was alarmed by the restoration of Brenner's initials to the obverse of the cent beginning that year, fearing that this would lessen the value of his investment." Chief Engraver Charles Barber is often portrayed as a jealous (and even villainous) figure by imaginative numismatic writers, especially when the subject concerned designs from outside artists. Barber is frequently credited with the prompt removal of the 'prominent' V.D.B. initials from the reverse; they returned to the Cent on Lincoln's shoulder in 1918, after Barber's demise. While a valuable issue in all Mint State grades, only once the MS66 tier is reached does the '09-S VDB truly qualify as a scarcity.

Intense luster, impressive color, NO spots, Very PQ. This is, perhaps, the most well-known collector date coin in the 20th century. With a mintage of just 484,000 pieces, the lowest of the series, it has the lowest mintage of any regular issue Small Cent, aside from the 1909-S Indian Cent. The 1909-S VDB enjoys a constant level of popularity from collectors because of its relatively low mintage, it’s first year of issue status, and the fact that 1909 was the only year the designer's initials were, at least for a while, placed on the lower reverse. The desirability of the issue is increased by its quality; unlike many San Francisco issues from the teens and twenties, the 1909-S V.D.B. tends to come well struck from fresh dies with consistent color. Calling it “The Holy Grail for Lincoln cent collectors,” David Lange, writing on the 1909-S VDB cent in his The Complete Guide to Lincoln Cents, refers to a story that is attributed to numismatic researcher George Fuld who "...recounts how coin dealer John Zug acquired some 25,000 uncirculated 1909-S V.D.B. cents directly from the San Francisco Mint at the time of their issue. Correctly surmising that these coins...would grow in value, he held onto them for several years. Around 1918, however, he decided to sell short [sic], realizing 1.75 cents apiece for his hoard. While of course we cannot be sure of Zug's motivations, perhaps he was alarmed by the restoration of Brenner's initials to the obverse of the cent beginning that year, fearing that this would lessen the value of his investment." Chief Engraver Charles Barber is often portrayed as a jealous (and even villainous) figure by imaginative numismatic writers, especially when the subject concerned designs from outside artists. Barber is frequently credited with the prompt removal of the 'prominent' V.D.B. initials from the reverse; they returned to the Cent on Lincoln's shoulder in 1918, after Barber's demise. While a valuable issue in all Mint State grades, only once the MS66 tier is reached does the '09-S VDB truly qualify as a scarcity.

1793 Chain 1C AMERICA AU53. S-3, B-4, Low R.3. EAC 40. Surfaces: The obverse surface has countless minute defects that appear to be almost entirely planchet flaws, representing an improperly refined strip of copper, a common problem in the first year of Mint operations. Sheet copper was not yet available from England, so available copper was scrap copper from local sources that Henry Voigt acquired. In his Encyclopedia of Large Cents, Breen discussed the problems with this locally available copper: "Scrap copper varied greatly in homogeneity, density, malleability, and hardness. This is partly from different trace elements and partly from the way the individual lumps had been treated in manufacture. This was a most unsatisfactory expedient; the coiner's department learned quickly that different ingots cast from it varied greatly , with far too many gas bubbles. Strip rolled from these ingots came out with too many cavities and laminations. Many surviving Chain cents accordingly show such flaws." The sophisticated collector will appreciate the planchet flaws as part of this coin's history and charm. A few tiny rim bumps are visible, and these appear to be the only post-strike imperfections. In direct opposition to the obverse, the reverse surface is nearly flawless. Only a few minute defects, rim flaws, and abrasions can be seen. Both sides have lovely medium brown color with traces of darker steel color on the high points. Considerable original mint frost remains, with splashes of lighter tan on the reverse, faded from original mint red. This example is a later die state. The obverse has prominent clash marks around and below the bust, and the reverse is flowlined with field roughening below UNITED STATES. The latest known die state of this variety, called Die State III in Breen's classification, displays heavy clash marks along Liberty's lips, chin, neck, and bust line. Breen suggested that these obverse clash marks, as seen somewhat on this example, were responsible for the "Liberty in chains epithet" sometimes given to the Chain cents. The Chain design was intended to show strength or unity of our new nation. Instead, the device was interpreted by many as representing slavery. Most of the mintage was lost or destroyed, so survivors are of various grades, usually lower quality. Porous or corroded pieces are frequently encountered. There is no question among specialists that Sheldon-3 is the most common Chain cent. Current rarity ratings for the Chain cent varieties suggest that the total surviving population of all varieties is 900 to 1,000 coins, with 400 to 500 examples of the S-3 and about 500 to 600 of all other varieties combined. Working under the assumption that the current rarity ratings are reasonably accurate, we can surmise that the original mintage occurred in about the same proportion. Approximately 18,000 examples of this die marriage were coined, with another 18,000 of the other three Sheldon numbers.

Lots of detail for VF25, Old Green Holder, R.4 PQ A large question surrounding this coin is whether or not President Washington supplied the silver. Research by Joel Orosz and Carl Herkowitz published in the 2003 Amer. Journal of Numismatics cited a memorandum by John A. McAllister, Jr. who related his interview with Chief Coiner Adam Eckfeldt: "In conversation with Mr. Adam Eckfeldt (Apr. 9, 1844) at the Mint, he informed me that the Half Dismes...were struck, expressly for Gen. Washington, to the extent of One Hundred Dollars, which sum he deposited in Bullion or Coin, for the purpose. Mr. E. thinks that Gen. W. distributed them as presents. Some were sent to Europe, but the greater number, he believes, were given to friends of Gen. W. in Virginia. No more of them were ever coined." Eric von Klinger in a June 13, 2005 Coin World review of the article entitled "Document Details Half Disme: Confirms that G. Washington was Source of Silver," wrote: "General Washington did indeed deposit silver for the 1792 half dismes." Orosz responded in a July 4, 2005 letter to the editor that: "We never claim in our article that we have proved that President Washington provided the silver used to strike the half dismes, as both the headline and the first sentence of von Klinger's article flatly state. In our article, we conclude that while the great preponderance of the evidence points toward Washington as the silver provider, the pieces of evidence that could prove he was - Washington's diary for 1792 and Acting Chief Coiner Henry Voigt's July 1792 account book - are unavailable. Washington was a long-time diarist, but the press of his presidential duties prevented him from keeping a diary in 1792. Voigt did keep an account book, but it was lost about a century ago, and no one knows where it is, or if it even still exists. Therefore, while the authors believe that all of the available evidence points to Washington, we cannot prove he was the donor beyond the shadow of a doubt."

Slight leg flatness from stacking or would be MS64. High Reliefs were struck in 3 blows of the dies on a medal press in the Philadelphia Mint. The first two strikings were made utilizing a plain collar, presumably to prevent the raised edge lettering from being disfigured from successive strikings. It was only during the third striking that the plain collar was replaced by the lettered collar to produce a complete High Relief Double Eagle with Lettered Edge. Due to the work-hardening of metal that results from the pressures of the striking process, the as yet incomplete coin was removed from the press after the first and second strikings to be annealed, or softened by heating. It is fairly well known that Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the "American Michelangelo," based his design for the double eagle on the winged goddess of Victory that forms part of the General William Tecumseh Sherman statue at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 59th Street in New York City. The winged goddess of Victory leads Sherman's horse. She wears a headdress and strides purposefully forward, her right arm stretched out before her, giving the entire monument a rhythmic, driving propulsion. Her eyes are depthless blanks, her expression simultaneously tragic and inscrutable. Similar to the traditional olive sprig in Liberty's left hand on the coin, Victory bears a palm branch in her left hand. One of Saint-Gaudens' great gifts--one that he shared with Michelangelo--was to be able to sculpt figures on a heroic scale, and yet imbue them with personality in the most human dimensions. It is perhaps less well known that Saint-Gaudens based the statue of Victory on the likeness of his mistress, Davida Clark. The General Sherman Monument, commissioned by the New York Chamber of Commerce in 1892, was the last large-scale work of Saint-Gaudens' cancer-shortened life. The final completed monument was installed in 1903. In the evolution from winged Victory to wingless Liberty, Saint-Gaudens managed to strip the nonessential from the female figure, while maintaining both her goddesslike grandeur and heroism as well as her powerfully human femininity. Removal of the wings and headdress allowed room for the de rigueur inscription above, focused more attention on the center of the coin, permitted Liberty's hair to blow freely in the breeze, and made more space beneath for the Capitol building.

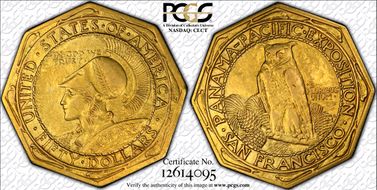

A handful of American commemorative issues have distinguished themselves among their peers. Some are known for being "firsts," such as the Columbian halves or the Louisiana Purchase gold dollars; some are famous for their innovations, such as the bimetallic Library of Congress ten dollar pieces; and still others have gained notoriety for their associations with boondoggle, such as the Cincinnati halves and Special Olympic dollars. A single issue, however, stands apart with its assortment of firsts and features. The 1915-S Panama-Pacific Octagonal fifty dollar piece is perhaps the most distinctive of the American commemoratives. The coins are impressive and imposing, and merely holding an example is an interesting experience. Their weight and substance are unlike anything else in the series, and for those who have had the privilege to handle an example outside of a holder, the flat, reeded edges and corners are a source of tactile fascination. The present piece offers a handful of unusual characteristics as well, chief of which is wear. While a number of worn or otherwise impaired examples of the Panama-Pacific fifty dollar octagonal coins are known, most such coins are ineligible for encapsulation. By contrast, the present coin, which may have worn slightly from being kept as a pocket piece, shows only light rub on the helmet, the rims, and the wing and legs of the owl. Abrasions are also present, namely one on Liberty's cheek and another on the right side of the owl, but the fields are comparatively well-preserved. Primarily yellow-gold surfaces offer occasional glints of green.

A handful of American commemorative issues have distinguished themselves among their peers. Some are known for being "firsts," such as the Columbian halves or the Louisiana Purchase gold dollars; some are famous for their innovations, such as the bimetallic Library of Congress ten dollar pieces; and still others have gained notoriety for their associations with boondoggle, such as the Cincinnati halves and Special Olympic dollars. A single issue, however, stands apart with its assortment of firsts and features. The 1915-S Panama-Pacific Octagonal fifty dollar piece is perhaps the most distinctive of the American commemoratives. The coins are impressive and imposing, and merely holding an example is an interesting experience. Their weight and substance are unlike anything else in the series, and for those who have had the privilege to handle an example outside of a holder, the flat, reeded edges and corners are a source of tactile fascination. The present piece offers a handful of unusual characteristics as well, chief of which is wear. While a number of worn or otherwise impaired examples of the Panama-Pacific fifty dollar octagonal coins are known, most such coins are ineligible for encapsulation. By contrast, the present coin, which may have worn slightly from being kept as a pocket piece, shows only light rub on the helmet, the rims, and the wing and legs of the owl. Abrasions are also present, namely one on Liberty's cheek and another on the right side of the owl, but the fields are comparatively well-preserved. Primarily yellow-gold surfaces offer occasional glints of green.

A handful of American commemorative issues have distinguished themselves among their peers. Some are known for being "firsts," such as the Columbian halves or the Louisiana Purchase gold dollars; some are famous for their innovations, such as the bimetallic Library of Congress ten dollar pieces; and still others have gained notoriety for their associations with boondoggle, such as the Cincinnati halves and Special Olympic dollars. A single issue, however, stands apart with its assortment of firsts and features. The 1915-S Panama-Pacific Octagonal fifty dollar piece is perhaps the most distinctive of the American commemoratives. The coins are impressive and imposing, and merely holding an example is an interesting experience. Their weight and substance are unlike anything else in the series, and for those who have had the privilege to handle an example outside of a holder, the flat, reeded edges and corners are a source of tactile fascination. The present piece offers a handful of unusual characteristics as well, chief of which is wear. While a number of worn or otherwise impaired examples of the Panama-Pacific fifty dollar octagonal coins are known, most such coins are ineligible for encapsulation. By contrast, the present coin, which may have worn slightly from being kept as a pocket piece, shows only light rub on the helmet, the rims, and the wing and legs of the owl. Abrasions are also present, namely one on Liberty's cheek and another on the right side of the owl, but the fields are comparatively well-preserved. Primarily yellow-gold surfaces offer occasional glints of green.

Very PQ, some mint bloom, perhaps not enough for RB designation. On 21 April 1787, the Continental Congress of the United States authorized a design for an official penny, later referred to as the Fugio cent because of its image of the sun shining down on a sundial with the caption, "Fugio" (Latin for "I flee"). The image and the word combine to mean "Time Flies". While most scholars attribute the sundial and link design to Benjamin Franklin, Breen recounts that Franklin only prepared the sketches from older representations. Whichever is correct, the obverse motif represents simplicity itself. By interpreting the central illustration, any child of the 1770s could "read" the obverse as follows: "Usable time (daylight hours, business hours) flies away; therefore mind your business." This symbolically states that time and daylight are fleeing, so don't waste them, hence "mind your business". This design had also been used on the "Continental dollar" (issued as coins of unknown real denomination, and in paper notes of different fractional denominations) in February of 1776. The Continental dollars, in turn, served as a model for the Fugio cents, struck 11 years later. Franklin also was the designer of the linked rings device seen on the reverse. It would seem that most historians believe that the word "business" was intended literally here, as Franklin was an influential and successful businessman. However, considering the full saying of "mind your own business," which would not have fit on the coin, it could also be interpreted as a statement of privacy. "Mind your own business" is a modern English saying which asks for a respect of privacy. It is often shortened, even aloud, to MYOB. In addition, "Mind your own business" can mean "Stop meddling in what does not concern you. Attend your own affairs. It's not polite to tell people what to do when you are not responsible for other people." The reverse side of both the 1776 coins and paper notes, and the 1787 coins, bore the third motto "We Are One" (in English). When the United States was reformed after the 1789 ratification of the 1789 Constitution, gold and silver coins bore the official motto of the new United States, E pluribus Unum, taken from the also non-religious 1782 Great Seal of the United States. In 1864, during the Civil War, the Union (North) introduced a 2-cent coin with the new motto "In God We Trust". In 1956, In God We Trust was mandated for all US currency, but more recently there have been calls for a return to the original mottos. Franklin's influence on contemporary society today is perhaps unrealized, yet it is enormous. Even though Franklin was never president, his influence on the nation was--and is--incalculable, and his ties with the portentous design on this delightful coin are many and deep. A Bank of New York hoard variety.

Very PQ, some mint bloom, perhaps not enough for RB designation. On 21 April 1787, the Continental Congress of the United States authorized a design for an official penny, later referred to as the Fugio cent because of its image of the sun shining down on a sundial with the caption, "Fugio" (Latin for "I flee"). The image and the word combine to mean "Time Flies". While most scholars attribute the sundial and link design to Benjamin Franklin, Breen recounts that Franklin only prepared the sketches from older representations. Whichever is correct, the obverse motif represents simplicity itself. By interpreting the central illustration, any child of the 1770s could "read" the obverse as follows: "Usable time (daylight hours, business hours) flies away; therefore mind your business." This symbolically states that time and daylight are fleeing, so don't waste them, hence "mind your business". This design had also been used on the "Continental dollar" (issued as coins of unknown real denomination, and in paper notes of different fractional denominations) in February of 1776. The Continental dollars, in turn, served as a model for the Fugio cents, struck 11 years later. Franklin also was the designer of the linked rings device seen on the reverse. It would seem that most historians believe that the word "business" was intended literally here, as Franklin was an influential and successful businessman. However, considering the full saying of "mind your own business," which would not have fit on the coin, it could also be interpreted as a statement of privacy. "Mind your own business" is a modern English saying which asks for a respect of privacy. It is often shortened, even aloud, to MYOB. In addition, "Mind your own business" can mean "Stop meddling in what does not concern you. Attend your own affairs. It's not polite to tell people what to do when you are not responsible for other people." The reverse side of both the 1776 coins and paper notes, and the 1787 coins, bore the third motto "We Are One" (in English). When the United States was reformed after the 1789 ratification of the 1789 Constitution, gold and silver coins bore the official motto of the new United States, E pluribus Unum, taken from the also non-religious 1782 Great Seal of the United States. In 1864, during the Civil War, the Union (North) introduced a 2-cent coin with the new motto "In God We Trust". In 1956, In God We Trust was mandated for all US currency, but more recently there have been calls for a return to the original mottos. Franklin's influence on contemporary society today is perhaps unrealized, yet it is enormous. Even though Franklin was never president, his influence on the nation was--and is--incalculable, and his ties with the portentous design on this delightful coin are many and deep. A Bank of New York hoard variety.

Very PQ, some mint bloom, perhaps not enough for RB designation. On 21 April 1787, the Continental Congress of the United States authorized a design for an official penny, later referred to as the Fugio cent because of its image of the sun shining down on a sundial with the caption, "Fugio" (Latin for "I flee"). The image and the word combine to mean "Time Flies". While most scholars attribute the sundial and link design to Benjamin Franklin, Breen recounts that Franklin only prepared the sketches from older representations. Whichever is correct, the obverse motif represents simplicity itself. By interpreting the central illustration, any child of the 1770s could "read" the obverse as follows: "Usable time (daylight hours, business hours) flies away; therefore mind your business." This symbolically states that time and daylight are fleeing, so don't waste them, hence "mind your business". This design had also been used on the "Continental dollar" (issued as coins of unknown real denomination, and in paper notes of different fractional denominations) in February of 1776. The Continental dollars, in turn, served as a model for the Fugio cents, struck 11 years later. Franklin also was the designer of the linked rings device seen on the reverse. It would seem that most historians believe that the word "business" was intended literally here, as Franklin was an influential and successful businessman. However, considering the full saying of "mind your own business," which would not have fit on the coin, it could also be interpreted as a statement of privacy. "Mind your own business" is a modern English saying which asks for a respect of privacy. It is often shortened, even aloud, to MYOB. In addition, "Mind your own business" can mean "Stop meddling in what does not concern you. Attend your own affairs. It's not polite to tell people what to do when you are not responsible for other people." The reverse side of both the 1776 coins and paper notes, and the 1787 coins, bore the third motto "We Are One" (in English). When the United States was reformed after the 1789 ratification of the 1789 Constitution, gold and silver coins bore the official motto of the new United States, E pluribus Unum, taken from the also non-religious 1782 Great Seal of the United States. In 1864, during the Civil War, the Union (North) introduced a 2-cent coin with the new motto "In God We Trust". In 1956, In God We Trust was mandated for all US currency, but more recently there have been calls for a return to the original mottos. Franklin's influence on contemporary society today is perhaps unrealized, yet it is enormous. Even though Franklin was never president, his influence on the nation was--and is--incalculable, and his ties with the portentous design on this delightful coin are many and deep. A Bank of New York hoard variety.

K-11, R.5. The last of fifty dollar slug varieties issued prior to the reorganization of the California mint as the United States Assay Office of Gold. The assay office was operated by Moffat & Co., which dissolved after its founder, John Little Moffat, left the firm in 1852. The new principles were Curtis, Perry, and Ward. Business continued as before, but the name of Augustus Humbert would no longer appear on the coins struck at the facility. This straw-gold slug has glimpses of rose-tinted luster within the wings, legends, and engine turning. The distributed marks are appropriate for 25 points of wear. Certified in a green label holder, and listed on page 353 of the 2008 Guide Book.

Full luster & rivets, slight friction on knee, PQ–. This 1916 quarter, struck in a transitional year, is one of the most famous 20th century silver rarities, with only 52,000 pieces minted. Few examples (in absolute terms) were set aside at the time of issue, making it a seldom-encountered date in all grades. However, because of the high prices the issue commands in all grades it is generally available in major auctions, which makes it seem more available than it really is. Much of the speculation about the redesign of the Type One Standing Liberty quarter centers around the alleged "indecency" of the exposed breast of Liberty, speculation that persists today. Novice historians (including Walter Breen) tended to overstate the role of the Society for the Suppression of Vice in the redesign process. In reality, someone with considerably more political clout was responsible for the design change. On April 16, 1917, Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo wrote to Representative William Ashbrook of Ohio to protest the Type One quarter design. On April 30, Ashbrook introduced McAdoo's bill before Congress. The document called upon the Mint to modify the original design by increasing the concavity of the fields and repositioning the eagle with relation to the stars. To support this legislation, McAdoo asserted (erroneously) that the Type One coins would not stack properly. This proposal became Public Law 27 on July 9, 1917 and specified that no major changes be made to the design other than those specifically stated. Since the approved modifications would have had a definite effect on the stacking qualities of the quarters, why did the Mint circumvent the law and further modify MacNeil's original design? While many numismatists see the jealous hand of Chief Engraver Barber at work, the real culprit was actually McAdoo himself, who had married President Woodrow Wilson's daughter in 1914. Through this familial alliance, as well as his position as Secretary of the Treasury, McAdoo hoped to springboard himself into the White House after Wilson stepped down. However trivial the complaints from the Society for the Suppression of Vice may have seemed to many Americans, an aspiring politician such as McAdoo could not afford to ignore them. Accordingly, the Treasury Secretary fabricated the charge of improper stacking to mask his real intentions. While the Mint did carry out the authorized modifications, it also significantly altered the basic design by using a chain mail vest to cover Liberty's exposed breast. The Treasury Department did not even attempt to modify Public Law 27 to reflect the change, but it did enter into the Congressional Record the fact that McAdoo did not like the Type One design--the only statement of truth in the entire process. While McAdoo's presidential hopes were dashed in the elections of both 1920 and 1924, the illegal changes he ordered for the Standing Liberty quarter remained in use until the design was retired in 1930.

Full luster & rivets, slight friction on knee, PQ–. This 1916 quarter, struck in a transitional year, is one of the most famous 20th century silver rarities, with only 52,000 pieces minted. Few examples (in absolute terms) were set aside at the time of issue, making it a seldom-encountered date in all grades. However, because of the high prices the issue commands in all grades it is generally available in major auctions, which makes it seem more available than it really is. Much of the speculation about the redesign of the Type One Standing Liberty quarter centers around the alleged "indecency" of the exposed breast of Liberty, speculation that persists today. Novice historians (including Walter Breen) tended to overstate the role of the Society for the Suppression of Vice in the redesign process. In reality, someone with considerably more political clout was responsible for the design change. On April 16, 1917, Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo wrote to Representative William Ashbrook of Ohio to protest the Type One quarter design. On April 30, Ashbrook introduced McAdoo's bill before Congress. The document called upon the Mint to modify the original design by increasing the concavity of the fields and repositioning the eagle with relation to the stars. To support this legislation, McAdoo asserted (erroneously) that the Type One coins would not stack properly. This proposal became Public Law 27 on July 9, 1917 and specified that no major changes be made to the design other than those specifically stated. Since the approved modifications would have had a definite effect on the stacking qualities of the quarters, why did the Mint circumvent the law and further modify MacNeil's original design? While many numismatists see the jealous hand of Chief Engraver Barber at work, the real culprit was actually McAdoo himself, who had married President Woodrow Wilson's daughter in 1914. Through this familial alliance, as well as his position as Secretary of the Treasury, McAdoo hoped to springboard himself into the White House after Wilson stepped down. However trivial the complaints from the Society for the Suppression of Vice may have seemed to many Americans, an aspiring politician such as McAdoo could not afford to ignore them. Accordingly, the Treasury Secretary fabricated the charge of improper stacking to mask his real intentions. While the Mint did carry out the authorized modifications, it also significantly altered the basic design by using a chain mail vest to cover Liberty's exposed breast. The Treasury Department did not even attempt to modify Public Law 27 to reflect the change, but it did enter into the Congressional Record the fact that McAdoo did not like the Type One design--the only statement of truth in the entire process. While McAdoo's presidential hopes were dashed in the elections of both 1920 and 1924, the illegal changes he ordered for the Standing Liberty quarter remained in use until the design was retired in 1930.

Full luster & rivets, slight friction on knee, PQ–. This 1916 quarter, struck in a transitional year, is one of the most famous 20th century silver rarities, with only 52,000 pieces minted. Few examples (in absolute terms) were set aside at the time of issue, making it a seldom-encountered date in all grades. However, because of the high prices the issue commands in all grades it is generally available in major auctions, which makes it seem more available than it really is. Much of the speculation about the redesign of the Type One Standing Liberty quarter centers around the alleged "indecency" of the exposed breast of Liberty, speculation that persists today. Novice historians (including Walter Breen) tended to overstate the role of the Society for the Suppression of Vice in the redesign process. In reality, someone with considerably more political clout was responsible for the design change. On April 16, 1917, Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo wrote to Representative William Ashbrook of Ohio to protest the Type One quarter design. On April 30, Ashbrook introduced McAdoo's bill before Congress. The document called upon the Mint to modify the original design by increasing the concavity of the fields and repositioning the eagle with relation to the stars. To support this legislation, McAdoo asserted (erroneously) that the Type One coins would not stack properly. This proposal became Public Law 27 on July 9, 1917 and specified that no major changes be made to the design other than those specifically stated. Since the approved modifications would have had a definite effect on the stacking qualities of the quarters, why did the Mint circumvent the law and further modify MacNeil's original design? While many numismatists see the jealous hand of Chief Engraver Barber at work, the real culprit was actually McAdoo himself, who had married President Woodrow Wilson's daughter in 1914. Through this familial alliance, as well as his position as Secretary of the Treasury, McAdoo hoped to springboard himself into the White House after Wilson stepped down. However trivial the complaints from the Society for the Suppression of Vice may have seemed to many Americans, an aspiring politician such as McAdoo could not afford to ignore them. Accordingly, the Treasury Secretary fabricated the charge of improper stacking to mask his real intentions. While the Mint did carry out the authorized modifications, it also significantly altered the basic design by using a chain mail vest to cover Liberty's exposed breast. The Treasury Department did not even attempt to modify Public Law 27 to reflect the change, but it did enter into the Congressional Record the fact that McAdoo did not like the Type One design--the only statement of truth in the entire process. While McAdoo's presidential hopes were dashed in the elections of both 1920 and 1924, the illegal changes he ordered for the Standing Liberty quarter remained in use until the design was retired in 1930.

1916-D 10C AU58. FULL luster and a strong strike, particularly on the bands. PQ. Whereas the Philadelphia Mint concentrated a great deal of effort on dime production in 1916, its Denver counterpart was preoccupied with the Barber quarter for most of the year. Among regular issue U.S. 20th century coins, the 1916-D has a remarkably low mintage of only 264,000 pieces. Only a few other key date issues have similar or lower mintages, and all are rarities in high demand. The 1916-D Mercury dimes were all released in November 1916, with production halted so that a sudden request for quarters could be filled. The Treasury Department submitted an order late in the year for 4 million quarter dollars. The quarters struck at Denver were, of course, the older Barber-design coins, and that is the only denomination the Mint produced for the balance of the year. Sometime prior to November 24, however, the Denver Mint did manage to deliver 264,000 dimes of the new Mercury design. The 1916-D, as the most famous key date in the Mercury dime series, is popularly called a rarity. In most grades, whether or not it deserves to be called "rare" depends on one's perspective; the early series collector, for example, who delves into the minutiae that differentiate the die pair with only five known from the one with thousands of survivors, might scoff at the idea of the 1916-D dime, a 20th century issue with a mintage of slightly over a quarter-million pieces, being considered rare. Four different reverse dies are known for the 1916-D dime coinage, and all four are illustrated in David Lange's The Complete Guide to Mercury Dimes. As one would expect, this issue's limited original mintage has earned it a place of honor in the pantheon of 20th century rarities. Circulated and Mint State examples alike are always in demand among the numerous collectors who specialize in this series. Demand for the 1916-D Mercury dimes is partly due to the low mintage, and partly due to their status as first-year-of-issue type coins. Many type collectors seek only first-year coins, while others choose only key dates for their collections.

O-102 Low R.6. The rarest regular-issue US silver coinage design and solid for the grade. The Draped Bust, Small Eagle half dollar is one of the most difficult type coins to obtain, arguably the most difficult silver type coin, but not as rare as the 1796 No Stars quarter eagle or the 1808 quarter eagle. These half dollars, bearing the dates 1796 or 1797, come from a paltry mintage of 3,918 pieces, about 250 of which have survived the ravages of time. Half dollars of 1796-1797 are one of the rarest U.S. type coins and certainly one of the most expensive in virtually all levels of preservation. Even the most advanced collections often lack this rarity, and when present, it is usually in the low to middle grade levels, as here, and/or impaired, unlike this original, problem-free piece. There are four varieties of Draped Bust, Small Eagle half dollar. The first 1796 variety (Overton-101) displays 15 obverse stars, while the second has 16 stars (O-102). The two 1797-dated varieties (O-101 and O-102) share the same obverse but have different reverses, differentiated by the alignment of the peripheral lettering in relation to the central devices. The reverse of the 1797 Overton-101 variety was originally paired with the 1796 15 stars and 1796 16 stars obverses. During its use with the latter obverse, the reverse die developed a crack from the tip of the palm leaf below the base of the F in OF through the right side of O to the milling. This reverse developed even more cracks shortly after it was paired with the 1797 obverse die (O-101) and soon began to break up (O-101a). The breakup of the reverse die used in the 1797 Overton 101 and 101a varieties resulted in the employment of a new reverse die. The O-102 reverse differs from the old reverse in that the peripheral lettering is slightly offset in relation to the wreath.

PQ! Original, Coin Alignment. Silver. Plain Edge. Die Alignment I (head of Liberty opposite the DO in DOLLAR). In addition to the artistic depiction of Liberty and the natural appearance of the eagle, one of the most distinctive elements of this 1836 Gobrecht dollar is the flight of the eagle upward at a sharp angle. Mint Director Robert Maskell Patterson carefully communicated what he wanted to artist Titian Peale by specifying that the eagle fly "onward and upward." To Patterson the positioning of the eagle was symbolic of the young republic. During the two striking periods in December 1836, the eagle maintained its upward angle of flight. The difference between the two December striking periods is the presence of a scratch above the eagle's wing, pointing toward the AT of STATES, that appeared on the die before the second batch of 600 coins was struck late in that month. A coin in Die Alignment I which lacks that die scratch is from the first striking period, a batch of 400 coins. The third striking period, in March 1837, was a batch of 600 coins dated 1836. They are commonly described as having been struck with a medal alignment (or medal "turn"), rather than a coin alignment (or coin turn). The third striking period began as expected, however, the reverse die slowly rotated from the "onward and upward" position to eventually level. A few coins have even been observed with the eagle's head slightly below a level horizontal plane. Coins from the first striking period are found in high grade more often than those from late December, as many were saved as souvenirs. That statement must, of course, be understood in the general context of coins that were struck and the low percentage of coins that were actually saved from the 1830s. In December 1839 a mere 300 additional original Gobrecht dollars, dated 1839, were struck. These were given a reeded edge and a medal turn, and they also were released into circulation. The head of Liberty is opposite the O in OF in the reverse legend, which defines what is known as Die Alignment IV (i.e., eagle flying almost level after a rotation around the coin's vertical axis, or "medal turn"). If the reverse displays no die evidence of a die crack through AMERI that means it's an original 1839 dollar, according to the Gray-Carboneau classification. Today most 1839 dollars seen are restrikes from the late 1850s and 1860s.